Emerald Fennell’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ is a film at war with itself: too loose to satisfy as an adaptation, too tethered to the text to fully stand on its own – but is it worth the trip to the cinema?

What emerges is an oddly declawed gothic romance that gestures at extremes – psycho-sexual fixation, feral passion, Brontë’s ruthless cruelty – only to retreat into something surprisingly tame, mild-mannered, and curiously audience-friendly. It’s neither a bracingly radical ‘Wuthering Heights’ nor a confidently original tragedy; it hovers uneasily in between, determined to sell ‘great love’ while sanding away everything that ever made that love frightening – or unforgettable.

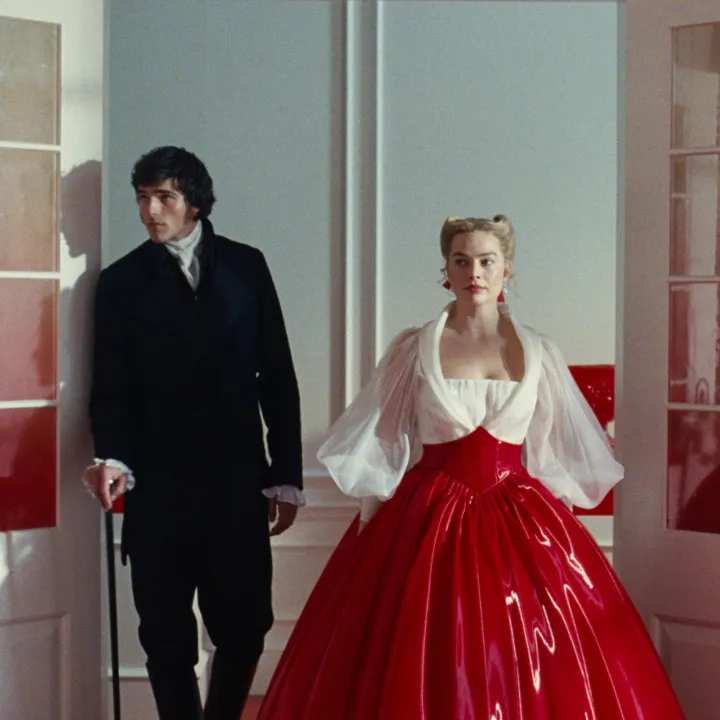

Two of our editors went to the cinema for Emerald Fennell’s hotly anticipated take – released for Valentine’s Day and starring Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi. Here’s what they made of it.

Read More: ‘Wuthering Heights’ (2026) Teaser Controversy: Artistic Liberty Or Provocative Misstep?

A Gothic Romance Without Its Guts

– Min Ji, Editor

Let’s be frank: I went in expecting provocation – Fennell’s work may divide, but it’s rarely dull – and instead found an approach defined by contradiction. The film loudly advertises itself as a bold, very loose vision, but the freedom mostly manifests as subtraction: more than half the book’s events and characters are simply gone, collapsing Brontë’s sprawling, multi-generational saga into something closer to a single, tragic adults-playing-teens romance that gestures at extremity, then retreats into something far more tame and straightforward.

In theory, that kind of ruthless paring back could yield a cohesive, distinctive take; in practice, it leaves the film feeling oddly hollow, like a ‘Wuthering Heights’ mood board shuffled into a ‘Romeo and Juliet’ template – the latter influence barely submerged, with the script practically underlining it in red (at one point, Alison Oliver’s Isabella speedruns through the famous misdelivered-letter device, which later becomes crucial to the climax). The result is less a provocative riff on Brontë but more ‘Wuthering Heights’ wearing ‘Romeo and Juliet’s’ clothes: the beats of star-crossed love are familiar, but the moral and emotional corruption that made the original so unsettling is diluted. The film feels too trapped by a need to be romantic, accessible, and commercially safe – trying to convince itself (and the audience) that vaguely-erotic missionary with some dirt and sweat is basically BDSM.

Sanding Down Heathcliff

Much has already been made of Jacob Elordi’s Heathcliff, and whether he reflects a fundamental misread of the character as a tragic romantic hero rather than a possessive, vengeful, and often hateful figure. However, watching the film, it becomes clear that Fennell does understand who Heathcliff is on the page – she simply makes a deliberate decision not to want that version. The film reframes much of the abuse he receives as a child not as an indictment of classism or racism, but as a twisted act of love on Cathy’s behalf, a choice that effectively reroutes systemic cruelty into personal, almost romanticised sacrifice.

Nowhere is this overhaul more glaring than in Heathcliff’s relationship with Isabella. In the novel, their dynamic is one of the clearest, ugliest expressions of his capacity for domestic and implied sexual violence. Here, the film goes out of its way to drag their interactions into the safest possible parameters of consent, devoting a too-long, heavy-handed sequence to Heathcliff repeatedly warning Isabella that he is a scoundrel, that he does not love her, and asking if she still wants this. Alison Oliver may give one of the more intriguing performances in the film, but her character is essentially sacrificed to preserve Heathcliff’s redeemability: she becomes a willing participant, even someone who seems to crave what limited cruelty he’s allowed to show.

That impulse to protect Heathcliff from true moral ugliness ripples outward. While the discourse has largely fixated on the decision to cast him as white, the film’s treatment of its actual characters of colour – most notably Nelly and Linton – ends up being more confounding. Linton is written off as a harmless, less-attractive obstacle to Cathy and Heathcliff’s great love, but Nelly is reconfigured as something closer to the story’s most actively cruel presence. Her shift from servant to illegitimate, semi-privileged companion could have opened space for a complex exploration of resentment, class aspiration, and thwarted desire. Instead, she’s flattened into an opportunistic, spiteful schemer: an almost asexual conniver whose actions more than inadvertently funnel Cathy toward a gruesome end. In a narrative full of historically cruel figures, making the woman of colour the most viscerally unlikable presence while softening Heathcliff with a doe-eyed Elordi feels, at best, unimaginative and, at worst, deeply misjudged.

Haunted By Her Own Hype

Calling this film ‘style over substance’ feels too neat, and not quite true. The problem isn’t Fennell’s looseness with Brontë – unfaithful adaptations can be exhilarating when they commit to a genuinely destabilising idea – but that, for all its liberties, this version repeatedly opts for the safer path. In the long, messy history of ‘Wuthering Heights’ on screen, directors have often taken the obvious shortcut of covering only Cathy and Heathcliff’s generation, and Heathcliff has overwhelmingly been played by white actors. Ironically, the bolder choice at this point might have been to return to the text: to honour the two-generation structure, to let Heathcliff’s dog-killing, bone-deep cruelty stand, to dwell in the novel’s ugliness rather than importing tired star-crossed-lover beats from elsewhere.

You can glimpse the more interesting film this might have been in its early, arresting equation of sex with death – the opening sequence, in which a hanged man’s gasps are indistinguishable from gasps of pleasure, promises a certain unsettling charge that suggests Fennell could push further. Yet any hint of a thornier film, of desire corroding into obsession or women hurtling towards destruction as their only form of agency, is sanded down. Rather than digging into that territory, the film gradually trades it for an endless procession of prettily arranged, static tableaux.

After the divisive nerve of ‘Promising Young Woman’ and the lurid excess of ‘Saltburn,’ ‘Wuthering Heights’ (2026) feels like the work of a director increasingly shadowed – and constrained – by her own reputation. Unfortunately, it seems that the main aspect of her work that Fennell has been able to consistently maintain is a refusal to follow through on her ideas. The more Fennell’s ‘style’ is framed as taboo, transgressive, and daring, the more she seems to pull her punches, landing on a film that hints at freakishness and ferocity while, almost self-consciously, stepping back – a ghost of a great, ugly love story that never quite dares to show its teeth.

A Fever Dream You Can Practically Feel

– Catherine, Editor-in-Chief

The marketing promised full-throated, capital-R Romance – a Valentine’s weekend gothic for those who like their period dramas drenched in sweat, grit, and ruin. In purely sensory terms, Emerald Fennell delivers. Her ‘Wuthering Heights’ is insistently physical: bodies battered by storms, every glance a potential spark.

The first impression, however, is a provocation. Fennell opens with a hanging, instantly fusing the morbid with the sexual to announce her thesis: grotesque, irreverent, uncomfortable – not the tasteful adaptation sought for literary credibility. It’s such an attention-grabbing shudder that it risks feeling like a stunt. The film does return to this mingling of passion and death, but the opening remains its most direct mission statement.

Once Catherine and Heathcliff are grown, the film becomes relentlessly erotic. Fennell’s camera dwells on damp skin, half-open mouths, the promise of dishevelment. It sometimes overplays its sensuality, as if terrified the point might be missed. Yet when it works, it’s because it understands desire as a colonising force, saturating the rooms, the fabrics, the air. Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi are the driving force of that effect. Their chemistry is deliberately, effectively blunt. Fennell bets that if you buy them as a destructive gravitational force, you’ll forgive much – and for many viewers, she’ll be right. They sell the relationship’s pull so convincingly that the film can indulge in overindulgence without tipping into parody.

And indulge it does. The costumes arrive with a certain theatrical confidence – not so much ‘historically accurate’ as ‘gowns, beautiful gowns’ in the fullest, gleeful sense. At times the styling threatens to upstage the drama; at others it is the drama, turning Catherine into a walking thesis on desire, self-dramatisation, and reinvention. The film’s world is bleak, yet flamboyantly so. If this sounds like a defense, it’s only half one. The film is strongest when committed to sensation – when willing to be strange, moist, vulgar, even a bit silly. It’s weaker when it tries to tidy that sensation into something emotionally digestible. Still: if you’re going for the big-screen immersion – the wind, the mud, the skin, the colour, the pageantry – this is where the film earns its price. It’s a movie that wants you to feel first and interpret later. Whether you leave grateful or irritated depends on how much you’re willing to be pushed around.

The Symbolic Overload (And Why It Almost Works)

Fennell’s cinema has never been shy, and here she embraces symbolism with the assurance of someone expecting you to read the film like an illustrated manuscript. Everything signifies: colours, textures, frames, objects positioned as indictments. Sometimes it’s thrilling – a director relishing the medium – and sometimes it’s so emphatic it feels bossy.

Red dominates, deployed insistently: on Catherine’s body, in interiors, in windows and floors, as desire and threat and wound. The film treats her not merely as protagonist but as the organising principle of its imagery. Even when the story nominally concerns shared doom, the visual language returns repeatedly to Catherine as the centre of wanting and self-destruction. Some compositions land with force: a figure sprawled like refuse on a checkered floor, romance rendered as strategy, a game with rules written by class and survival. Fennell finds shots that communicate interior life in a single glance – obvious, but effective.

When the film moves into Thrushcross Grange, wildness yields to containment. The rooms are large but read as display, not freedom. The imagery grows obsessed with enclosure – glass, vases, frames within frames – articulating a particular horror: luxury as a beautiful trap. Catherine is costumed like an object, placed like an object, treated like one, and the visuals insist you notice. Religious iconography runs through the film, whether by design or the material’s gravity. Pleasure and punishment merge; devotion resembles self-harm; sin becomes aesthetic. The opening’s fusion of sex and death colours everything, a film fascinated by suffering’s erotic charge – pain rehearsed as feeling’s proof.

Here intelligence and heavy-hand wrestle. Fennell makes ideas tactile yet also explains them with a highlighter, unwilling to trust the audience. Some motifs repeat past resonance, as if anxious you might misunderstand. Yet the ambition is hard to dislike. Even when the imagery is too loud, it’s an attempt to make ‘Wuthering Heights’ cinematic rather than merely scenic. Fennell wants the story to live in images, not just dialogue, and she’s best when making meaning through surfaces – fabric, blood, weather, architecture. If the film ultimately frustrates, it’s not for lack of ideas; it’s because it sometimes mistakes insistence for depth. The imagery constantly tells you this matters. The question is whether those images accumulate into something emotionally inevitable – or simply into a gallery of clever pictures.

Race, Cruelty, And The Limits Of Fennell’s Fantasy

No modern ‘Wuthering Heights’ can avoid the Heathcliff question, and this film’s choices invite debate rather than sidestep it. Brontë’s language leaves room for interpretation; critics have run with that ambiguity for decades; audiences arrive primed for an argument. Fennell’s casting and storytelling decisions effectively declare what kind of conversation she’s willing to have. Jacob Elordi’s Heathcliff is presented foremost as an object of desire. The film wants him dangerous, but in a way that remains consumable – broodiness with glamour, cruelty with a limit. That isn’t inherently illegitimate; cinema is full of romantic monsters. The problem is that ‘Wuthering Heights’ isn’t simply about a magnetic man ruining people. It’s about what happens when grievance hardens into systematic harm. When you soften that, you change the story’s moral weather.

The film’s treatment of Isabella is telling. The novel gives you a relationship that is grim, coercive, and steeped in violence. Fennell seems aware of the discomfort – and, rather than sitting with it, works to recast it through the language of consent and choice. Alison Oliver plays Isabella with an eerie, doll-like oddity that’s genuinely watchable, but the character’s function becomes complicated: she absorbs the film’s kinkier impulses while protecting Heathcliff from the full ugliness of his actions. It’s daring in surface terms, oddly conservative in outcome.

Then there’s the matter of who carries the story’s nastiness. The film race-bends some roles in a way that could, in theory, open interesting avenues – an opportunity to interrogate belonging, class aspiration, and the economics of intimacy in a household trapped by hierarchy. In practice, the racial implications feel underthought. The film flirts with race’s presence, acknowledges it briefly, then retreats into aesthetic colourblindness, unwilling to follow through. That retreat matters because the story is already about power. When you shift certain characters’ racial identities while simultaneously sanding down the central man’s worst impulses, you risk creating an accidental hierarchy of sympathy – where the primary romantic object remains protected, and other figures become foils or moral scapegoats. Even if the intention is purely stylistic, the effect has political weight.

Here Fennell’s authorial signature becomes both draw and limitation. She makes films that revel in toxic appetites, stylish depravity, the thrill of watching people behave terribly. That sensibility can be exhilarating – and is, in parts – but it also comes with blind spots. A fantasy that is vivid, white, and self-contained can look, from the outside, like a refusal to engage with the material’s wider implications. And yet it’s not as simple as ‘bad therefore worthless.’ This film is often entertaining. It has glamour, audacity, real star power. It gives you the cathartic pleasure of watching a lavish mess commit to being one. If you go in expecting a rigorous moral excavation of Brontë, you’ll be disappointed; if you go in expecting Fennell – a feverish, decadent, self-aware gothic-romance nightmare – you may find it does exactly what it says on the tin.

The question, then, isn’t whether it ‘respects’ the novel. It’s whether you’re willing to accept the trade: a ‘Wuthering Heights’ filtered through a very specific, very personal fantasy, where the feelings are maximal, the images are loud, and the nastiness is curated. For some, that will be the point. For others, it will feel like a gorgeous dodge.

Friday Club. is where every day feels like Friday. We spark conversations that are both trendy and thought-provoking, exploring topics that truly matter while staying true to ourselves. We’re all about honesty, tackling tough subjects head-on, yet we never forget to embrace the fun life has to offer.